What is meant by sovereignty in the digital age? And what is the nexus to an innovative and strengthened Swiss financial sector? Those are the questions this article will try to answer.

Defining Digital Sovereignty: Legal and Political Approaches

According to the definition of the Whitepaper of the Swiss Data Alliance (SDA) published in 2024 (available in German, Italian and French), digital sovereignty comes into play where (1) digital processes (2) exert an influence on Swiss territory and (3) Switzerland as a state is institutionally affected. Hence, digital sovereignty is not about every administrative IT decision. It concerns situations in which the Swiss state, as an institution, is systemically affected. The sovereignty debate should primarily focus on preserving or improving the state’s “Handlungsfähigkeit”, its ability to act, decide and protect national interests. “We must resist the urge to make digital sovereignty a catch-all term. It should guide state capacity, not dominate technical decisions” said Christian Laux, Vice President at SDA, at the panel discussion “Digitale Souveränität” held on 11 June 2025 at Casino Bern (see as well the related Announcement).

Broader and politically motivated definitions of “digital sovereignty” are also used. There, digital sovereignty is referred to as the ability to act autonomously in the digital space and maintain control over data, systems and processes. This definition understands “sovereignty” in the sense of “autonomy” or “independence” and is much broader. As a consequence, and in analogy to electricity, health or traffic infrastructure, some call for state-run IT ecosystems. The SDA proposes a more subtle test: What qualifies as a systemic event? And which dependencies truly impair institutional autonomy?

For the purposes of this article, we follow the narrower SDA definition advocating for a clear distinction between legal and political factors. To enable such distinction, the SDA has established a basic document “Digitale Souveränität – Grundlagen” (available in German, Italian and French) addressing specific areas, such as the term "independence" or the topic of open source software.

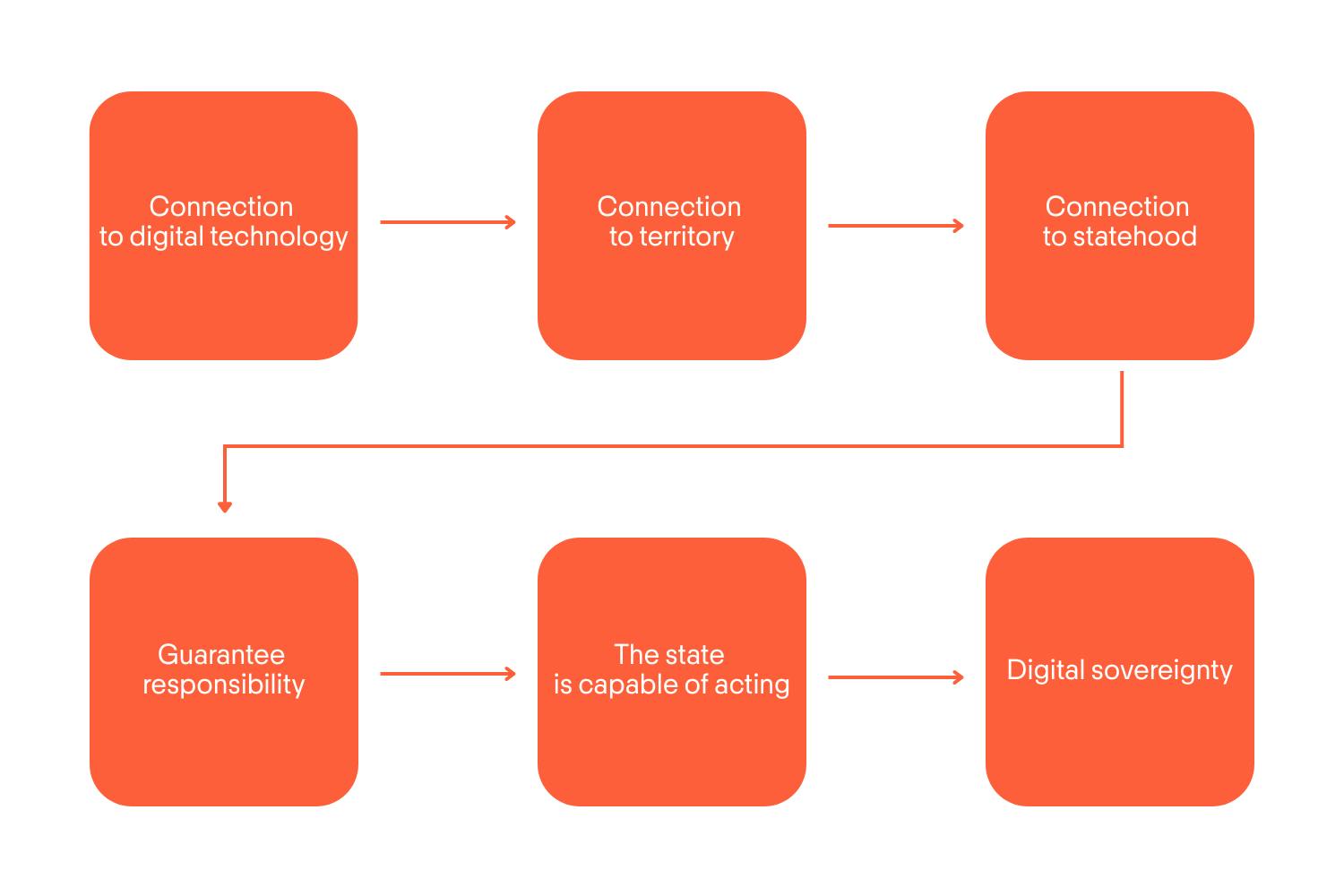

The mentioned basis document defines digital sovereignty as the ability of a state in the digital space to define its jurisdiction internationally (taking into account the recognized sovereignty of other states), to shape its internal affairs, and to defend both. A helpful decision tree in Annex 3 provides guidance in the form of a decision tree as to whether digital sovereignty is intact or not:

The decision tree consists of the following steps:

1. Is the case related to digital matters?

2. Is the case relevant to Switzerland’s interests (e.g., Swiss rooted organizations in humanitarian help, the Swiss government agencies, or the Swiss population)?

3. Is there an existing problem that affects Switzerland’s ability to act? The question of the ability to act is a preliminary question to understand whether there is actually a problem that needs to be examined more closely. Where there is no problem, there is no need to optimize. However, there may be issues that are “too big” for those who have to shape everyday life. This could affect a statehood matter.

4. The question of statehood determines whether the state must or wants to address an existing problem. In both cases, the question of sovereignty then arises.

5. Now (only now) is the question of digital sovereignty being addressed. Where it does not exist, the aim is to be able to recognize this (retrospectively) and do something about it (prospectively).

Source: “Digitale Souveränität – Grundlagen” by Swiss Digital Alliance, p. 46

In the context of the financial sector, the question would consequently follow the above decision tree. Particularly, the following questions arise: What digital dependencies truly impair state autonomy (digital sovereignty) when it comes to a competitive and innovative Swiss financial sector and infrastructure as a whole? Does the state’s capacity to act extend to financial institutions and their data, operations and technology and if so, to which ones and how? The answer varies depending on the case in question, e.g. Switzerland’s interests in remaining a leading, competitive and digital international financial center, in attracting foreign companies and talent, in growing its GDP accordingly. If the result is that digital sovereignty is in fact affected and not (or no longer) intact, it is upon the legislator to deal with it.

As a high-level example – albeit dealing with operational resilience and hence only indirectly with digital finance, competitiveness or innovation – serves the FINMA Circular 2023/1 regarding Managing Operational Risk and Ensuring Operational Resilience. It provides that in- scope financial institutions must ensure that their operational resilience is adequate and that their organization can deliver the required minimum business service outcomes in times of “severe but plausible” disruption. According to the circular, some disruption scenarios can however only be managed with state involvement (e.g. pandemics, wars, long-term power shortages). For these situations, financial institutions should do as much as they can in advance to make sure that they can keep working and are as operationally resilient as possible, if the disruptions occur. The circular provides further for more nuanced and stricter rules when it comes to systemically important banks.

One Complex Reality, Different Perspectives

As mentioned above, the notion of digital sovereignty lends itself to more than one interpretation – each shedding light on a different facet of what it means to retain control in an interconnected world.

Some argue that digital sovereignty requires a deliberate strengthening of public technological capacities, particularly through the adoption of Open Source Software (OOS). From this perspective, Europe's growing reliance on foreign digital infrastructure is not merely a technical issue, but a strategic vulnerability. Sovereignty, in this view, entails equipping states with the tools and autonomy to shape and steward their own digital ecosystems. This was the position expressed by Matthias Stürmer during the SDA panel on digital sovereignty hold in Bern in June 2025.

Others maintain that the essence of sovereignty lies not in the elimination of all external dependencies but in the ability to govern them with resilience, legal clarity and institutional accountability. What ultimately matters is not full independence, but the capacity to maintain control, ensure compliance and safeguard public values through well-framed, enforceable systems. This line of reasoning was notably defended by Christian Laux at the same event previously mentioned.

In 2024, Prof. Dr. Matthias Stürmer’s, Head of the Institute Public Sector Transformation at the Bern University of Applied Sciences, handed over the study “Technological Perspective of Digital Sovereignty” to the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), making a scientific contribution in the context of postulate 22.4411 “Strategy Digital Sovereignty of Switzerland” by Councilor of States Heidi Z'graggen. The report reveals the following: digital sovereignty is currently very limited in Switzerland. There are individual approaches in this country to establish control over data and developing IT systems independently. However, no systematic approach or concrete implementation is yet visible. The situation is different in neighboring countries such as Germany and France, where digital sovereignty is regularly discussed at the highest level of government and which invest substantially in the independence of their digital technologies and IT infrastructures. According to the study, Switzerland has numerous opportunities to increase its digital sovereignty effectively and cost-effectively if it follows the report’s recommendations and implements accordingly activities in this direction.

Everyday Digital Management: A Matter of Responsibility

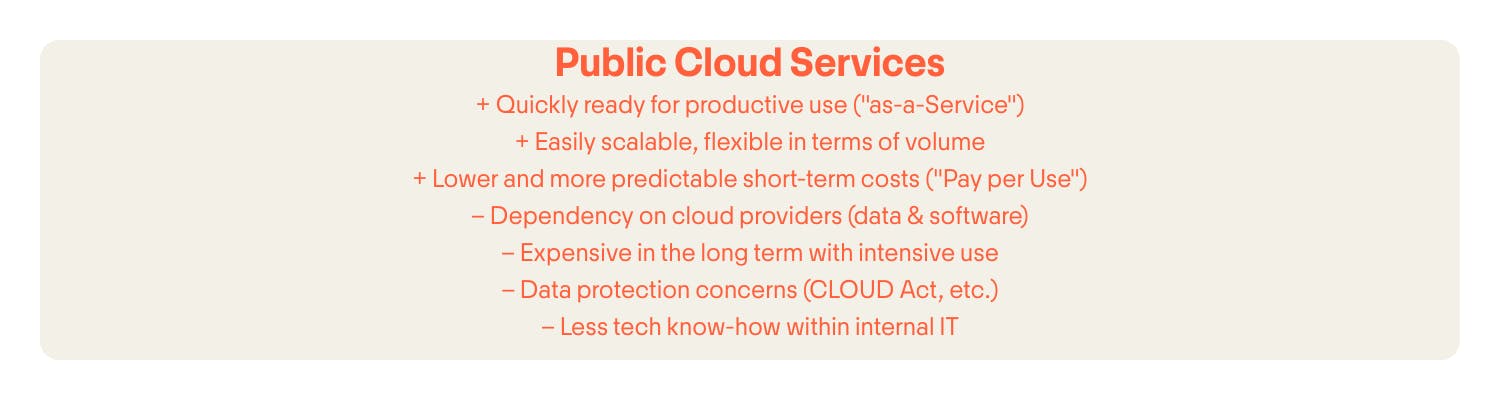

In most scenarios, decisions about software procurement, cloud usage or data storage fall under the responsibility of individual agencies or institutions. The state's role, then, is not to control all decisions centrally but to act when systemic risks arise or when the state has assumed a constitutional guarantee obligation.

This nuance is especially relevant considering recent developments. The Canton of Geneva has quietly reinforced its reliance on Microsoft infrastructure, sparking debate around transparency and strategic dependency. In Lucerne, the planned introduction of Microsoft 365 into cantonal administration has been publicly contested. And at the federal level, the Confederation has fully implemented Microsoft 365 across its departments – a major step that brings operational benefits but also raises legitimate questions about long-term autonomy.

These decisions, while operational in nature, raise systemic questions: what happens if access to core infrastructure is disrupted for political reasons?

Although not directly related to a state’s interests in staying innovative and competitive in digital finance matters, a recent case illustrates just how high the stakes can be: Microsoft reportedly blocked access to the mailbox of Karim Khan, Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC is an independent international organization based on the multilateral Rome Statute of 1998. Its legal personality is recognized under international law. While the full circumstances remain disputed, the incident highlights a critical vulnerability, when mission-critical international (supra-state) functions depend on infrastructure controlled by foreign private companies, national and in this case international sovereignty becomes imperative.

This brings us to the broader question of sovereign cloud infrastructure. As public services and sensitive data increasingly migrate to the cloud, ensuring that hosting, access and governance remain under democratic oversight is no longer optional. Several European countries have launched dedicated initiatives – such as GAIA-X or national “clouds of trust” – to offer secure, legally compliant alternatives to dominant hyperscalers (very large global cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure or Google Cloud, operating massive data centers worldwide and offering virtually unlimited computing and storage capacity). In Switzerland, similar debates are gaining traction, even if large-scale public deployments remain limited for now. In this evolving landscape, digital sovereignty is not just about ideology – it is about the ability to build, maintain and govern critical infrastructure on terms set by public interest and democratic accountability.

In parallel, Switzerland is also investing in alternative digital models rooted in open science. This summer, EPFL and ETH Zurich announced the forthcoming release of a fully open, publicly developed large language model – trained on the “Alps” supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS), using carbon-neutral electricity. Designed for transparency, multilingual capability and accessibility, the model illustrates how sovereign infrastructure and open collaboration can together foster trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (AI). While not a substitute for operational cloud services, it signals a path forward: one where public institutions develop and control the digital tools they rely on – aligned with democratic values, scientific rigor, and long-term autonomy.

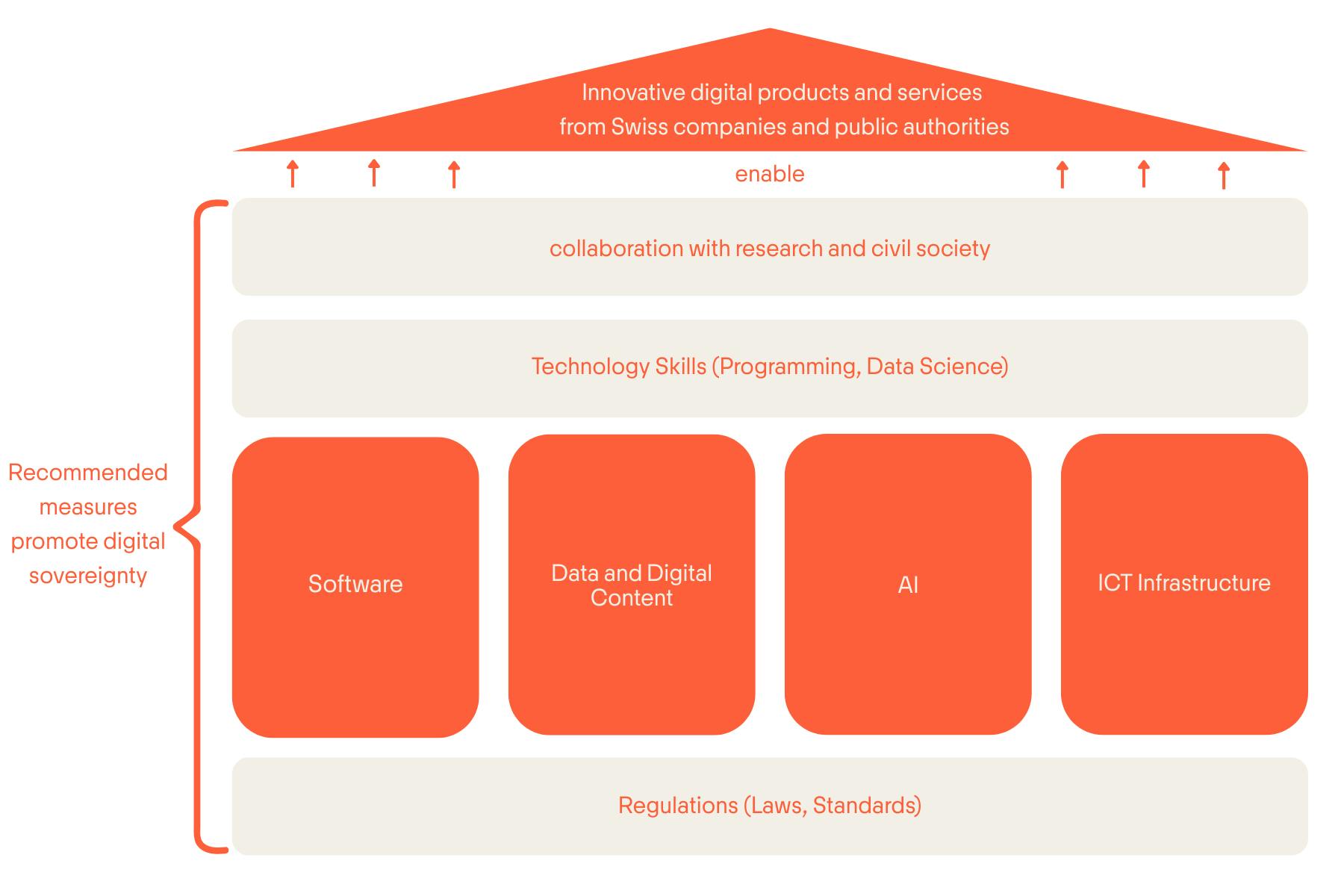

Source: Study “Technological Perspective of Digital Sovereignty” by Bern University of Applied Sciences (2024), p. 9

Political Momentum and Public Concern

The political momentum started with the postulate by Councillor of States Heidi Zgraggen on digital sovereignty (22.4411) instructing the Federal Council to define “digital sovereignty” and assess the status for Switzerland. The Federal Council responded that it would comment on this postulate in a report and present the results of its work. Apart from that, digital sovereignty is also relevant under the “Digital Switzerland 2025”strategy, as yearly updated. For example, information and cyber security as well as OSS are amongst the current focus topics.

There continues to be criticism and calls for faster and more comprehensive action to strengthen Switzerland's digital sovereignty. Notably, National Councilor Andri Silberschmidt submitted a detailed interpellation to the Swiss Parliament (No. 20253704) in June 2025. His questions also target the heart of the digital sovereignty debate: How should Switzerland define and defend its digital autonomy? What (financial) infrastructures are critical? Should procurement be reformed to prioritize local or European providers? And how can Swiss SMEs and startups (including of course smaller financial institutions or fintechs) access large-scale public IT projects?

Zgraggen and Silberschmidt’s moves signal a turning point: digital sovereignty is moving up on the political agenda, the political debate might eventually also lead to the introduction of new or amendment of existing laws and regulations.

Pluralism Over Centralization

A central recommendation from the SDA is to approach this topic through pluralistic, inclusive dialogue rather than through unilateral mandates. The organization cautions against assuming that open source, Swiss-made solutions, or local providers are automatically better. Each case must be evaluated on its own merits.

This pluralism does not mean relativism. On the contrary, it demands greater precision. According to the SDA, Switzerland needs to differentiate clearly between political goals and legal obligations. This distinction avoids governance deadlock and allows institutions to act swiftly within a known framework. As legal expert Christian Laux puts it, "digital sovereignty can be an important guideline, but in many cases, we could simply call it regulation, and nothing would be lost.”

Trust, Governance and the Human Factor

Whether in the context of the Covid app, the re-launched E-ID project or ongoing Open Finance infrastructure considerations, the Swiss public expects transparency and accountability. Preserving this trust over time requires that technologies be deployed in ways that ensure interoperability, scalability, competitiveness, user autonomy and remain consistent with their original purpose – even in circumstances of exception. The Covid app, for example, raised concerns not necessarily due to its design but because it was introduced in an exceptional context where certain liberties were temporarily constrained. If technology – or in this case digital tools – begin to subtly steer user behavior or shift in purpose during crises, rebuilding trust afterwards may prove difficult. Open-source software, while not a silver bullet, can contribute to this trust when supported by competent institutions and robust architectures. Its value lies not in ideology, but in its flexibility, auditability and its potential to reduce vendor lock-in – provided it is properly implemented. In other words: open source software does not lead to greater digital sovereignty, but it can be an effective means of creating options for action in the area of everyday life, reducing the need for a state to act (see “Digitale Souveränität – Grundlagen” of SDA, p. 36).

Conclusion: A Call for Accelerated Clarity and Choice

Digital sovereignty is not a rhetorical shield: it is a responsibility. To be meaningful, it must be anchored in precise definitions, systemic relevance and the goal of preserving the state’s capacity to act.

Once the political discourse about whether the state’s capacity to act is sufficiently preserved, depending on the debate’s results, this will eventually lead to amended or new Swiss legislation. And then, of course, the above-mentioned responsibility becomes an obligation.

In a world where geopolitical pressure can materialize in the form of a blocked email account of a representative of a highly institutionalized supra-state body – as in the case of ICC Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan – relying entirely on private foreign infrastructure is not merely a technical issue: it is a matter of statehood.

This is why Switzerland should now engage in a rigorous, pluralistic reflection on its digital future. Exploring and investing in open source alternatives is not an ideological stance, it might be a strategic necessity, provided it is done with competence, transparency and proper governance. It comes along with having a sufficiently skilled workforce to deal with development and maintenance of any such applied open source software.

Digital sovereignty, if understood narrowly and acted upon wisely, can help to protect the core of what makes a state resilient: its ability to make decisions, serve its people and remain accountable – on its own terms. The cited study of Bern University of Applied Sciences proposes several recommendations to do just that – while at the same time enable continued digital financial innovation:

Source: Study “Technological Perspective of Digital Sovereignty” by Bern University of Applied Sciences (2024), p. 27

The Bern University of Applied Sciences has published a study on digital sovereignty, available here (in German).