Stablecoins On the Rise

As of June 2025, the market capitalization of blockchain-based stablecoins for payment purposes – the focus of this article – exceeded USD 250 billion (see coverage in NFT evening or CoinGecko). Tether (USDT) and Circle (USDC) are the dominators, but new players enter to gain market share – so far predominantly with USD-pegged stablecoins. Ripple for example launched its RLUSD back in December 2024 – as of June 2025 it nears USD 380 million market cap, a significant start for a new player.

For risk diversification and other reasons, there is a demand for stablecoins pegged to non-USD currencies such as the British Pound Sterling, the Canadian Dollar, the Euro, the Japanese Yen or the Swiss Franc. On 1 July 2025, AllUnity, a joint venture between DWS, Flow Traders, and Galaxy, announced that it has been granted an E-Money Institution (EMI) license by BaFIN, empowering AllUnity to issue Germany’s first BaFin-licensed EUR stablecoin (EURAU) in compliance with the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) framework. MiCAR but also proposed U.S. legislation (for details see below) accelerate the mainstream and institutional adoption of all stablecoin types, driving their deeper integration into the global financial system.

Why are Stablecoins Needed?

According to the latest Payment Methods Survey by the Swiss National Bank (SNB), the shift from cash to cashless payment methods is continuing. Debit cards are the most frequently used payment method, while mobile payment apps come to play in almost one of five payments at physical points of sale (POS). However, the large majority (95%) of the people surveyed in Switzerland want to keep using cash. Stablecoins provide less privacy than cash, so do they have a chance in Switzerland? Are they even needed? Pascal Egloff, Head of the Center for Banking & Finance at OST - Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences affirms: “A well-functioning stablecoin is crucial for the continued advancement and innovation of both the blockchain sector and the financial services industry. Only through truly digitized means of payment can the full efficiency gains of distributed ledger technology be realized. Without stablecoins that align with market demands and regulatory frameworks, the widespread adoption of this technology, along with its potential to transform financial systems, could be severely constrained”.

To a similar conclusion comes the Swiss Bankers Association (SBA) in its report on “Stablecoins in Switzerland – An Overview of the Opportunities and Risks of Stablecoins Issued by Swiss Banks” (April 2025) specifically on a potential Swiss franc-backed stablecoin. In sum, stablecoins are generally viewed as efficient, innovative, low-cost and secure means of payment, with the potential to streamline (cross-border) transactions and support digital asset trading and future decentralized finance (DeFi) services.

Ultimately, it’s about having a choice. While cash has its benefits and will stay a good (Swiss) friend, digital assets such as stablecoins complement the money landscape. It should be up to the people to decide what kind of money serves them best (be it for personal or for business use) and how much they want to protect their privacy. This is also one of the key recommendations of the scientific study of TA-Swiss on “New Digital Swiss Francs – Our Money of the Future” (see condensed version in English of study , p. 20).

In the network of online money - TA Swiss Study

From the perspective of issuers, it is about making money. Everything a user can do with a stablecoin – trade, earn, or (for purposes of this article) pay – increases its utility. The greater the utility, the greater the retention and float income (i.e. the revenue generated by stablecoin issuers from the interest earned on the reserves held to back the stablecoin's value). Further practical insights about utility examples can be found in the Stablecoin Practitioner's Guide by Tokenized Asset Coalition et al.

In sum, the scope of stablecoin payment use cases is not limited to cryptocurrency transaction settlements, but extends to international remittances, B2B cross-border transactions, digital payments, e-commerce, and much more (see Deloitte Tohmatsu Consulting research paper of March 2025). Stablecoins are a key element for innovation in the digital financial system because they combine stability, efficiency and new DLT-based applications. They promote the development of new business models, particularly in the area of DeFi, and drive the digitalization of payment transactions and asset management. At the same time, they challenge legislators and regulators to create a framework that enables innovation but controls risks.

Regulatory Boosters like MiCAR or the GENIUS Act

Policy makers and financial regulators around the world are introducing frameworks for stablecoins, most notably the EU and the US. The rules are far from aligned “leaving many private-sector organizations with an interest in capitalizing on the growing stablecoins market frustrated at what they perceive as slow and inconsistent rulemaking” notes GlobalGovernmentFintech.

The following provides a brief overview of some key parameters of the EU’s MiCAR and the US Genius Act (for informational purposes only, the decisive regulatory texts should in any event be consulted):

EU: MiCAR is in force since December 2024, aligning the framework across the 27-member states. If DLT-based, e-money tokens (EMTs) are regulated as e-money and crypto-assets, hence subject to both MiCAR and the E-Money Directive. National competent authorities and the European Banking Authority (EBA) supervise the issuers. At least 30% of the reserves must be held in trust accounts. Permitted are only investments in liquid, low-risk assets. MiCAR requires a white paper for EMTs, detailing the project, risks, and rights for token holders.

US: In June 2025, the Senate passed the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins Act of 2025 (GENIUS Act) which triggers the next phase: reconciling it with the House of Representatives. The GENIUS Act clarifies that payment stablecoins do not qualify as securities or commodities, and issuers not as investment companies under federal law. Federal and state regulators oversee compliance of a proposed dual regime: issuers with > USD 10B market cap require federal oversight; smaller issuers can opt for state regulation if standards are “substantially similar”. The proposed law requires a strict 1:1 reserve backing with high-quality liquid assets. Reserves must be segregated from operational funds and subject to monthly certification. The draft law’s approach centers on ongoing financial and operational disclosures rather than a one-time comprehensive white-paper document as required under MiCAR. More information on the draft bill can also be found here.

Given the different regulatory approaches and broad range of stakeholders involved in stablecoin operations (e.g. at issuance, transfer/exchange or redemption), there is a general need and call for more harmonized (and enforced) rules on an international level. This is also a clear recommendation in the Deloitte Tohmatsu Consulting research paper “Analysis For the Healthy Development of Stablecoins ”, commissioned by the Financial Services Agency Japan with inputs from academic professionals, March 2025, p. 39 et seqq., for download link see below).

Illicit Use - The Flip Side of the (Stable)Coin

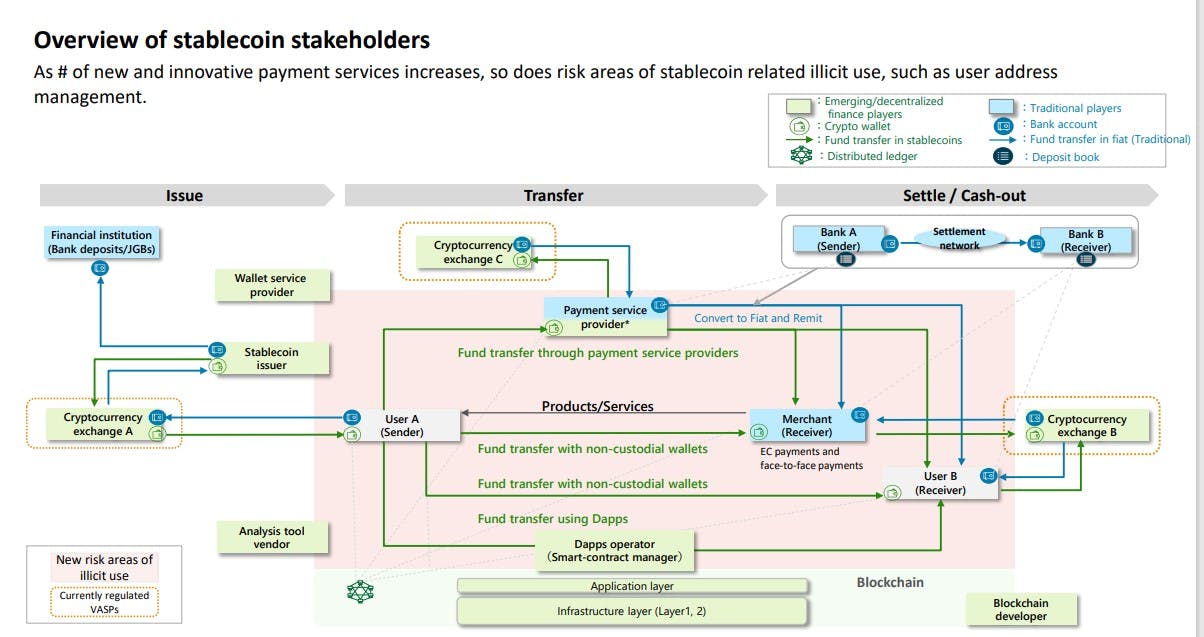

As stablecoins increase in market share, illicit use of stablecoins – such as anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) – are an increasing international concern, especially in view of the broad range of stakeholders, the nature and speed of the transactions and corresponding risks and challenges. The cited Deloitte Tohmatsu Consulting research study provides for a comprehensive stakeholder map and lists the corresponding risks and challenges for the relevant actor groups. Methods used in laundering crypto-assets include mixing, which conceals the route of fund transfers, and chain-hopping, which involves multiple chains. Harmonized and enforced international rules and industry-wide collaboration to track and prevent illicit use are essential as mentioned.

"Analysis For the Healthy Development of Stablecoins", a Deloitte Tohmatsu Consulting Research Paper (March 2025)

Stakeholder map in Deloitte Tohmatsu Consulting research study (April 2025)

Healthy Countermeasures, incl. Compliance-by-Design

The programmability of stablecoins and smart contracts introduces the potential for ‘programmable compliance’ (see e.g. Digital Euro Association Working Group’s “The Role of Stablecoins in Financial Sovereignty” of 2025, p. 31 et seqq.). Certain regulatory requirements (e.g., transaction limits, holding restrictions, automated checks against sanction lists, or pattern matching algorithms to flag illicit activity) can be embedded directly into code. This ‘compliance-by-design’ could offer supervisors granular visibility into financial flows, while simultaneously improving end-user privacy through technologies like zero-knowledge proofs or fully homomorphic encryption (a form of encryption that allows computations to be performed on encrypted data without first decrypting it). In response for example to mixing, stablecoin issuers may implement mechanisms to extend the effectiveness of their blacklists to Layer 2 blockchains, analysis tool vendors using machine learning for pattern analysis, and wallet providers offering alert functions for prevention. At the time of transaction, the sanctioned address and smart contract of the mixing service provider can be checked (i.e. in real-time). In response to chain-hopping, blockchain analysis tools are available to graphically analyze and track cross-chain transaction information.

Noteworthy are the following results of the Deloitte study:

It cannot be conclusively said that the expansion of stablecoin use has led to an increase in illicit activities. Rather, it has been confirmed that it is necessary to understand the overall picture, including the instant exchangeability with the underlying (crypto) assets, not just the management system of stablecoins themselves.

To address the illicit use of stablecoins, measures such as the use of blacklist functions by issuers can be considered. However, there are limitations to what issuers can do alone, and cooperation with analysis tool vendors and authorities is required.

The scope of actors involved in stablecoin transactions has expanded to include not only cash-out, but also the exchange for goods and services, involving payment service providers, merchants, and other peripheral businesses. Therefore, it is expected that all stakeholders will further fine-tune their measures according to the roles of each actor. There are also still many underdeveloped aspects (and remaining issues) in terms of regulations and incentives for stakeholders. For instance, when an incident is discovered, responses in practice vary, such as immediately freezing assets if there is suspicion (and unfreezing them if the suspicion is cleared later) or consulting authorities before freezing assets (based on multiple analysis tool vendor interviews). Considering the instantaneous cash-out nature of stablecoins, there is a need to strengthen real-time countermeasures.

The State of Stablecoins in Switzerland

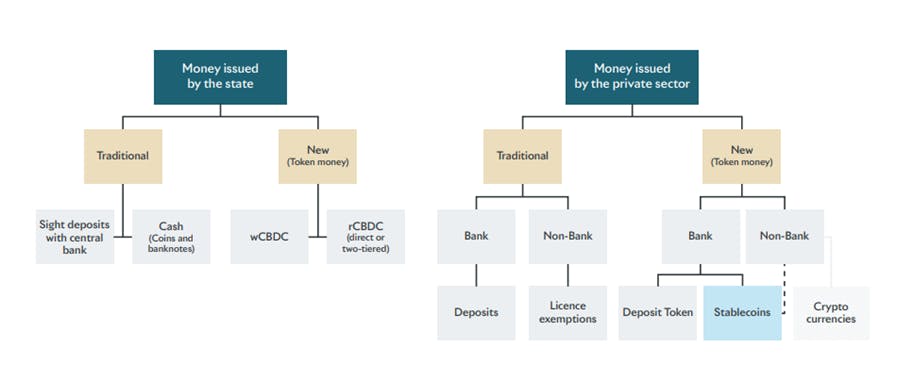

In Switzerland, stablecoins would be deemed as “private money” and can currently be issued by banks or, subject to certain requirements and bank guarantees, by non-banks.

The Swiss Money Taxonomy

Source: SBA report on stablecoins, based on TA-Swiss study on the digital Swiss franc (both reports from 2025)

There is as of today no specific regulation on stablecoins. FINMA applies the existing financial market laws, in particular the Banking Act (BA), the Collective Investment Schemes Act (CISA) and the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) based on the economic function and risk profile of each stablecoin project. With FINMA Guidance 06/2024 “Stablecoins: Risks and Challenges for Issuers of Stablecoins and Banks providing Guarantees” of July 2024, FINMA clarified its practice, supplementing its earlier ICO guidelines. In short, stablecoins are treated as deposits under the BA if the underlying assets (e.g., fiat currencies) are managed at the issuer's risk. Issuers must then either have a banking license or obtain a bank guarantee to secure the deposits. When the underlying assets of a stablecoin is managed at the holders’ risk, they would be classified as collective investment schemes (under CISA). Due to the usually intended payment purpose, the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) almost always also applies.

According to FINMA, the qualification of the issuer’s liability to the respective stablecoin holder as a deposit under banking law leads to a permanent business relationship under AMLA. To address the risks and fulfil AMLA requirements, contractual and technological transfer restrictions are required for the issuance of stablecoins by supervised institutions. FINMA’s views its current practice to be aligned with existing laws, the principle of technological neutrality (same business, same risks, same rules) and preventing stablecoins to circulate as anonymous accounts or bearer shares. However, there has been partial push-back by the industry as well as academic scholars on FINMA’s interpretation of applicable existing law (see e.g. “12 Recommendations and Demands for Politics, Government and Industry ” by the Swiss Blockchain Federation or recent scientific academic article by Prof. Dr. Mirjam Eggen and Dr. Christian Sillaber with an in-depth comparative analysis with MiCAR).

Government’s New Proposal “Innovative Business Models”

The “Digital Finance: Areas for action 2022+” report instructs the regulators to review the existing framework, particularly with regard to fintech players and their business models. The Federal Council’s recommendations of the evaluation report on licensing in accordance with Art. 1b Banking Act (“Fintech licensing”) of December 2022 further provides for certain elements of the license to be amended. The regulator is thus preparing a draft bill to amend existing financial market laws as needed. The draft bill will be submitted for consultation in 2025.

Conclusions

Stablecoins are on the rise, boosted by international regulatory developments providing welcomed legal clarity and harmonized rules for at least those impacted larger territories. The proposed GENIUS Act is narrower in scope than MiCAR, focusing on payment stablecoins with strict 1:1 backing, continuous information obligations, and dual federal/state oversight, while MiCAR provides a broader, harmonized regime for all e-money tokens using DLT, with layered requirements from both MiCAR and the E-Money Directive, the requirement for an upfront white-paper and backing requirements of at least 30%. MiCAR ring-fences its market (see FIND report on UZH conference “Cross-Border Financial Services – Is This The End?”), while the US GENIUS Act allows foreign issuers to offer and sell stablecoins in the US through an intermediary if the issuer is subject to requirements “comparable” to the US GENIUS requirements, and subject to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) supervision, among other things (for further information see Sullivan Cromwell update here).

In Switzerland, the domestic framework conditions are also work in progress. So far, a factor limiting stablecoin growth in Switzerland seems to be the current FINMA expectation to know the identity of every stablecoin holder at all times, not just at issuance or redemption. According to the SBA report “Stablecoins in Switzerland” there has been “criticism that FINMA has tightened its practice beyond the existing international standard and the money laundering principles applicable to date, to the detriment of issuers.” It will be interesting to see if and how the Swiss regulator will address the current framework conditions going forward. The public consultation process is expected to be kicked off during 2025. In the course of the legislative process, parliament will also have the opportunity to assess the positions set out in the FINMA Guidance 06/2024. In any event the important work by reputable scholars and industry associations, the keen interest of regulators to stay competitive and the extensive practical knowledge of early stablecoin adopters give reason to hope for a global convergence on “compliance-by-design” and related best practices.

Glossary

AML/CFT

Anti Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism

Analysis Tool Vendors

Analysis tool vendors specialize in analyzing data recorded on blockchains to provide information that aids in monitoring and tracking crypto-asset transactions. They offer services focused on identifying addresses used for illicit use by analyzing publicly available information outside the blockchain.

Decentralized Applications (dapps)

Applications built on a decentralized network that combine smart contracts with front-end user interfaces.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi)

A set of alternative financial markets, products, and systems operated using crypto-assets and "smart contracts" (software) built with technologies that potentially reduce or eliminate the need for centralized or intermediary processes.

DLT

Distributed ledger technology, allows data to be stored and managed decentrally on multiple computers, making transactions transparent, secure and tamper-proof.

FATF

Financial Action Task Force

Fiat money

Central bank-issued legal tender that, unlike commodity money, is not backed by physical goods or natural resources

Hosted /custodial wallet

Client wallet where the financial intermediary with VASP activities has access to the client’s VAs

KYC

Know Your Customer. A procedure implemented by financial intermediaries to verify the identity of clients, assess and monitor client risk and prevent illegal activities such as money laundering

OFAC

The Office of Foreign Assets Control

Payment Service Providers

Payment service providers are companies or institutions that offer services such as funds transfer, settlement, and clearing in commercial transactions. This includes traditional entities such as credit card companies, electronic money issuers, mobile payment providers, and banks, as well as entities that mediate exchanges when crypto-assets or stablecoins are used as payment methods.

Smart Contracts

A program is deployed on the blockchain that automatically executes a transaction as soon as the conditions agreed by the contracting parties have been met. Smart contracts remove the need for intermediaries and manual intervention. Smart contracts are executed by the blockchain network’s nodes. For all results to be valid, the execution results must be recorded on the blockchain.

Smurfing

Breaking down a large sum of money into smaller transactions that fall below the reporting thresholds in order to conceal the true value of the transaction and avoid detection by ML/TF regulatory authorities

Travel Rule

Based on FATF Recommendation No 16, this rule requires financial institutions with or without VASP activities to share client data with each other when carrying out crossborder transactions

Unhosted / non-custodial wallet

Wallet in which virtual assets are held directly by an individual without any form of third-party access

VASP

Virtual asset service provider

Wallet Providers

Wallet providers are entities that offer services for storing, sending, receiving, and managing crypto-assets. Wallets are broadly categorized into custodial and non-custodial wallets, and the risks associated with the business vary depending on the type of service provided.